“We have an ambition as a football group to have an organisation that is global and that will have multiple clubs as part of it,” said Khaldoon Al Mubarak, the chairman of the City Football Group, in 2014 after they added Japanese side Yokohama F. Marinos to the network of international clubs that were a part of the City Football Group (CFG). Yokohama were the fourth club to be added to their portfolio. Since then, there have been six more in countries across the world, ranging from India to Uruguay, China to France and beyond.

The origins of the CFG stretch all the way back to 2008, when the royal family of Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates, purchased Premier League side Manchester City, making them the then richest club in football — they are currently fifth behind Real Madrid, Barcelona, Manchester United and Bayern Munich. This was an unimaginable feat for the club, often believed to be Manchester’s ‘other team’ compared to the dominance of United during that period. The early part of that decade saw them fighting in the second division of English football. Now, the fans were dreaming of winning the Champions League.

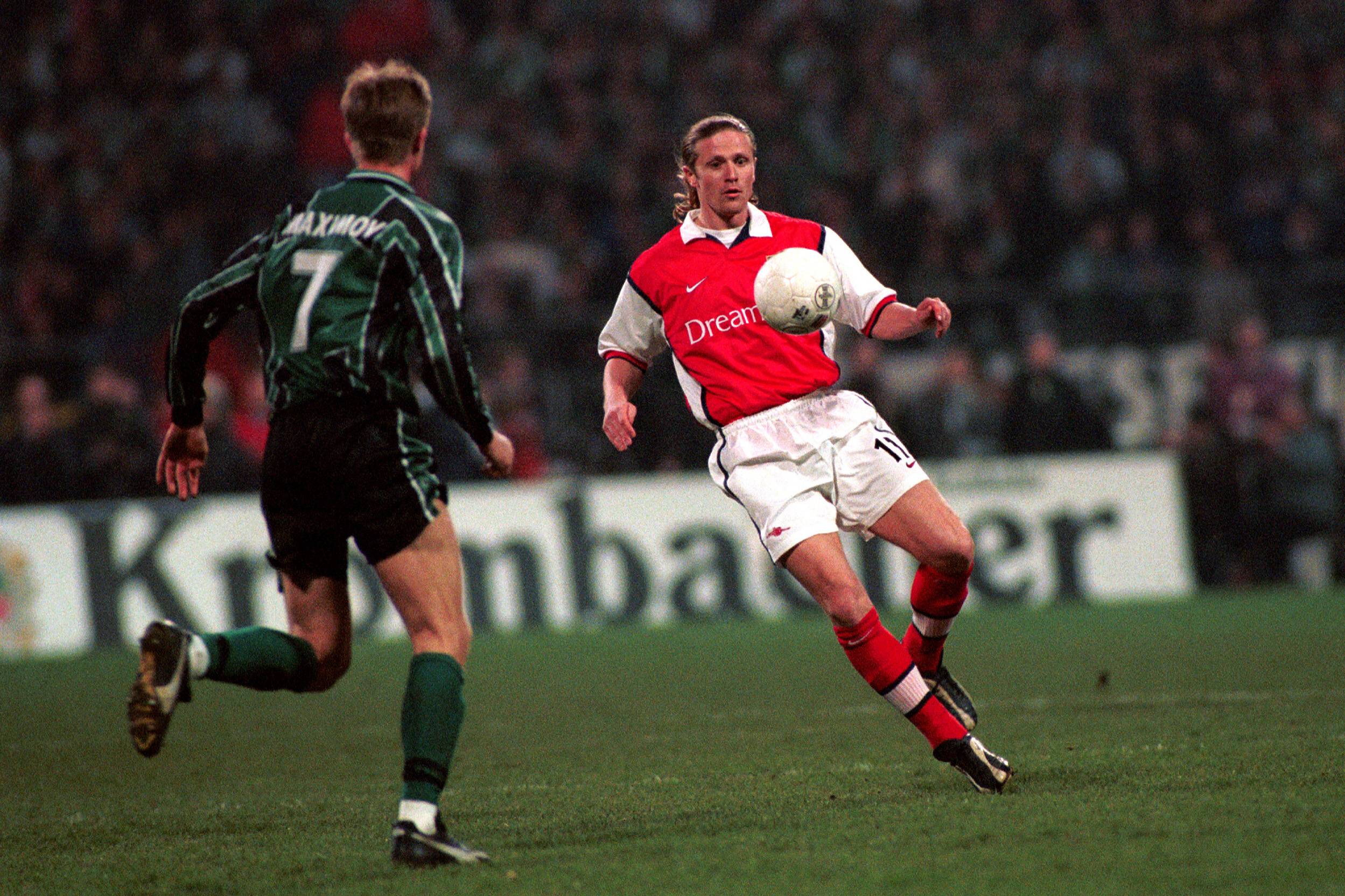

Success was slow, however. After a few big transfers including that of Carlos Tevez from rivals Manchester United and Emmanuel Adebayor from Arsenal, it took until 2011 and the appointment of Roberto Mancini as head coach for City to win their first trophy — an FA Cup win. This was their first trophy in 35 years and was the sign of things to come. A league title followed a year later in circumstances that have since become legendary, paving the way for what would be the norm for City in the years to follow.

In 2013, the City Football Group was born as a holding company for its sports properties, owned by the Abu Dhabi United Group, which itself was owned by Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Deputy Prime Minister of the UAE and the son of Sheikh Zayed, the founder of the nation. Part of the CFG were two crucial cogs: Txiki Begiristain, the director of football, and Ferran Soriano, the club’s Chief Executive Officer — both at Manchester City. Both joined in 2012 and set out the blueprint for City and the CFG’s style of football that has made the group so dominant in recent years.

Formerly of Barcelona, it was the group’s vision to see their team playing the way Pep Guardiola’s side were at the turn of the decade, and in appointing Soriano and Begiristain, they were a step closer to their vision. That very year, Soriano played a huge part in the CFG going global. In partnership with Major League Baseball franchise New York Yankees, the CFG created an MLS expansion club in the same city: New York City FC. Wearing the same colours as their cousins in Manchester and having the same shirt sponsors, Etihad Airways, the group were establishing a global identity.

🏴 Manchester City

🇺🇸 New York City

🇦🇺 Melbourne City

🇯🇵 Yokohama F. Marinos

🇺🇾 Club Atletico Torque

🇪🇸 Girona

🇨🇳 Sichuan Jiuniu

🇮🇳 Mumbai CityCity Football Group have now extended their ownership to India, with Mumbai the eighth club to be taken over by the company 👀

— GOAL News (@GoalNews) November 28, 2019

Soon after, they added Australian A-League club Melbourne Heart to their portfolio, controversially changing their name to Melbourne City FC. Additionally, the Australian side also temporarily added Spanish forward David Villa to their ranks for four games — he agreed to join New York City after leaving Atlético Madrid but had to move to Australia on loan as the club hadn’t been formed yet. This was one of the benefits of the CFG — clubs in the network could easily transfer players between them.

The ease at which deals could be completed between clubs in the CFG gave many an advantage — not all clubs in Australia have access to top talents like David Villa; not all in MLS can get a hold of Frank Lampard. What the CFG were doing wasn’t illegal by any means, but the opportunity to move top players around with ease gave them a massive edge.

Three clubs in three continents and three massive football markets was impressive, but the CFG wasn’t done yet. Now with Soriano and Begiristain on board, they were able to begin establishing a playing style and in 2016, having already won two league titles, two League Cups and one FA Cup, they got their biggest target: Guardiola, with the Spaniard agreeing to sign from Bayern Munich, taking over from Manuel Pellegrini. City may have spent over £840m between 2008 and 2015 to bring in top players like Kevin De Bruyne, David Silva and Sergio Agüero, but Guardiola was undoubtedly their biggest acquisition.

With him, they were also able to set a clear playing style across all clubs as their network continued to grow. Guardiola was one of the most successful managers of the decade and signing him was a statement of intent from the CFG. Along with the three clubs they owned outright in Manchester, New York and Melbourne, the CFG now had a stake in Japan (Yokohama F. Marinos), Uruguay (Montevideo City Torque) and Spain (Girona) by 2017. In the coming years, they would also add clubs in China (Sichuan Jiuniu), India (Mumbai City FC), Belgium (Lommel SK) and France (Troyes) to their portfolio.

Manchester City & Pep Guardiola pic.twitter.com/LnxR6sH303

— Sporx (@sporx) July 8, 2016

The CFG have used this network to develop their players. In 2019, Douglas Luiz was sold from Manchester City to Aston Villa for £15m after joining them two years prior and never having played for them. He spent those two years out on loan at Girona, did well for the Spanish side but was then let go. Similarly, Angeliño joined City in 2014 and had several loan spells away before joining PSV Eindhoven in 2018. A positive season there caught Pep Guardiola’s attention and he returned to City. But after struggling to break into the first-team, he would join RB Leipzig on two separate loan spells, where he is now a regular. A permanent move to the German side is now very likely.

These deals have been profitable to Manchester City and it provides them with a good network to develop their players in a less-pressured environment. If they are able to handle the pressure, there’s always a chance that they play for City, but if things don’t go as planned, they are likely to be sold at a profit.

Speaking to SportsPro Media, the CFG’s Chief Football Operations Officer, Omar Berrada, said: “When we set out as City Football Group, the three big markets we always had in mind were the US, China and India, right from the beginning. For the most part, we were able to go to the US very quickly. We then thought about China and India, but ultimately, we didn’t want to go to those markets without having the right partner. We’ve got into a position now where we’re very comfortable with the people that we’re working with in such key markets, markets that have grown so quickly over the last years from an economic perspective and have interesting socio-demographics.”

This hunger for expansion has raised the issue of sportswashing, a debate that has only grown traction in recent months with Saudi Arabia’s failed takeover of Newcastle United. In the years since the Abu Dhabi funded takeover of Manchester City, many have believed the club is a tool for its owners to cleanse the UAE’s poor image with regards to human rights violations and their poor treatment of migrant labour. In 2018, Amnesty International criticized the club after a sponsorship deal was struck with Arab firm Arabtec: “As a growing number of Manchester City fans will be aware, the success of the club has involved a close relationship with a country that relies on exploited migrant labour and locks up peaceful critics and human rights defenders.”

It’s sportswashing, pure & simple.”@felixjakens of @amnesty tells me the campaign group is “incredibly concerned” about Newcastle United’s impending sale to a consortium including Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, given the country’s poor human-rights record pic.twitter.com/XGuaHoi4iX

— Dan Roan (@danroan) April 16, 2020

This has often been an issue, not just with supporters, but with officials working with the CFG as well. The UAE’s disputed record when it comes to the treatment of migrant workers and more strikingly, the laws against the LGBTQ community have always been under the spotlight. Many believe this to be one of the main motives of the CFG: use football and the world’s most popular football league (the Premier League has mass commercial appeal globally, including football betting) to improve the image of the UAE on the international stage.

“Abu Dhabi/UAE vulnerabilities put in play: gay, wealth, women, Israel,” read an email from Simon Pearce, a director at Manchester City when discussing the possibility of starting an MLS franchise in 2013 with his colleagues at CFG. Over the years, sportswashing has most prominently been evident in the Berlin Olympics of 1936 and the World Cup of 1978, but the CFG are involved in it on a far more commercial and global scale.

In adding so many clubs to their network, a benefit for many of them was the easy transfers between players and coaches, and New York City are one of the biggest beneficiaries. Over the years, the likes of Patrick Viera (as a coach) have moved from Manchester to New York. Viera was previously working with City’s youth teams before he was appointed as the head coach of the MLS franchise. They have since had a huge amount of access to European coaching and tactical expertise, giving players and teams outside of the Premier League a chance to improve.

Patrick Viera has signed a three-year deal to become head coach of New York City FC. pic.twitter.com/7zZytbO9bh

— Unibet Racing (@UnibetRacing) November 9, 2015

Venezuelan midfielder Yangel Herrera is an example of one such player who has benefitted from CFG’s expansive network. He agreed a deal to join Manchester City from Atlético Venezuela (another club the CFG were keen on adding to their network) in 2017 but never made an appearance for them. Instead, that year, he joined New York City and became one of their most impressive midfielders, playing in nearly every game. To this day, he is contracted to Guardiola’s team, but loan spells in Spain with Huesca and Granada meant that he has never played in England. It has worked out well for his career, however, opening a pathway to his national team.

Speaking to The Athletic, Claudio Reyna, the former US international who was previously the sporting director of New York City FC, said: “It’s a great sounding board for us to bounce ideas off of and get feedback. From a scouting perspective, football strategy, sports science, medicine — we have the access to tap into all of that. Whether it’s going there physically and visiting or reaching out on an email or the phone, my staff has the ability to do that and share information, which is really, really helpful.”

New York is also the home for a group similar to the CFG: Red Bull. Having commenced their football operations in 2005, the energy drinks company expanded to form clubs in Austria, Germany, the USA, Brazil and Ghana (now defunct). With a similar strategy: a set playing style, identical crests and colours, they controversially succeeded in their project, with Red Bull Salzburg reaching the Europa League semi-final in 2018 and RB Leipzig reaching the Champions League semi-final in 2020. Spearheaded by the now-departed Ralf Rangnick, who was the sporting director of both Salzburg and Leipzig whilst also being the head coach of the German side on two separate occasions, their teams play an exciting brand of football.

• 2009 = Founded

• 2010 = Promoted to 4th Div

• 2013 = Promoted to 3rd Div

• 2014 = Promoted to 2nd Div

• 2016 = Promoted to Bundesliga

• 2017 = Bundesliga runners-up

• 2020 = #UCL semi-finalistsWhat an incredible rise RB Leipzig have had in 11 years!

🙌🙌🙌 pic.twitter.com/7WTQhO9WCL

— Micky Green’s Tips (@_MickyGreenTips) August 19, 2020

It is in New York where the two brands come head-to-head, and while Red Bull have the upper-hand in the rivalry, boasting some impressive results including a 7-0 win, it is the CFG-backed club that arguably have the brighter future. With Red Bull focusing mainly on their two European clubs, their investment in New York has reduced, giving rise to the belief that New York City FC could soon become the region’s top club. Regardless, this is where two of modern football’s biggest villains meet, but they have certainly improved the football scene in the city.

Indeed, it is the Red Bull example that perhaps provides an indicator as to why City haven’t invested in more than one European club. While they do have stakes in clubs in Spain, Belgium and France, the only club they own outright is Manchester City, and a UEFA rule that Red Bull had to circumvent possibly explains why. In 2017, Red Bull faced issues when both RB Leipzig and Red Bull Salzburg qualified for European competitions at the same time. UEFA rules indicate that two clubs with the same ownership structure would not be able to participate in Europe and that the lower-placed club would drop out.

That would’ve meant that Salzburg (who were champions of Austria) would’ve been able to play in Europe that season while RB Leipzig (runners-up in the German Bundesliga) would be disqualified. Similar instances occurred in 1997 when Slavia Prague were given a pass to play in the UEFA Cup ahead of AEK Athens — both were owned by investment company ENIC. Furthermore, in 2001, Paris Saint-Germain were allowed to play ahead of Swiss side Servette due to their ownership by television company Canal+.

When it was Red Bull’s turn, however, they made a few structural changes, moving a few directors across clubs while also ensuring Rangnick was working with just Leipzig, all of which meant that UEFA were forced to let them play. For the CFG, that may well also have to be the case. City will use their sister clubs across Europe as developmental outfits — a factor exemplified by the loan move for their goalkeeper Daniel Grimshaw to Lommel in Belgium on the final day of the 2020 summer transfer window — and it could be beneficial for up-and-coming academy players.

As such, their main objectives for these European sides will be to have them playing in the top-flight of their respective countries, so that their players can play at the highest possible level. But greater success for their feeder clubs could bring with it conflicts on the European stage similar to those Red Bull had to navigate last year.

On the topic of UEFA, the CFG and Manchester City are no strangers to the governing body of European football. Right from the early years of Sheikh Mansour’s extravagant investment, City have been under the spotlight of Financial Fair Play. The first instance was when Manchester City struck a 10-year £400m sponsorship deal with Etihad Airways, the national carrier of the United Arab Emirates and also a company closely linked with Sheikh Mansour. That led to a hefty £49m fine from UEFA, with the sanction later reduced to £16m.

In 2018, Football Leaks (via Der Spiegel) obtained documents that claimed Manchester City were in breach of FFP regulations. In February 2020, they were banned from the Champions League for two seasons for:

- Committing serious breaches of FFP regulations by overstating the value of the sponsorship deals in their accounts submitted to UEFA between 2012 and 2016

- Failing to cooperate in the investigation of the case by the Club Financial Control Body.

That ban was eventually overturned by the Court of Arbitration for Sport in July 2020, but this long-battle between the club and the controlling body has been bitter.

It's official…

Man City are allowed to compete in next season's Champions League after the Court of Arbitration for Sport ruled to lift the two-year ban previously imposed.

The club will have to pay a €9m fine. pic.twitter.com/G1Gl5zmYSs

— Football on TNT Sports (@footballontnt) July 13, 2020

Over time, more companies got involved with the group. In 2015, the CFG sold a 13% stake at $400m to China Media Capital just a few months after Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Manchester. This only raised suspicion of more state involvement, but no evidence of any wrongdoing was found. As such, Al Mubarak only focused on the football side of things: `Football is the most loved, played and watched sport in the world and in China, the exponential growth pathway for the game is both unique and hugely exciting.”

This may not be a group liked by many and it may feel like an artificial presence in football, but this style of ownership is likely to be the way of the future. Red Bull have had unbridled success with the ownership model after years in the energy drinks line and now the CFG have a plan in place for domination on all fronts. In the years to come, more groups resembling Red Bull and the CFG will rise — there are already murmurings of Liverpool owner John W. Henry selling shares of the Fenway Sports Group to RedBall, a group that has already made investments in clubs like AZ Alkmaar and Barnsley. Football is a profitable sport at the top level, and combined with a firm sporting project, it’s not a surprise that states and businesses are so keenly interested in the potential glory at the end of it.